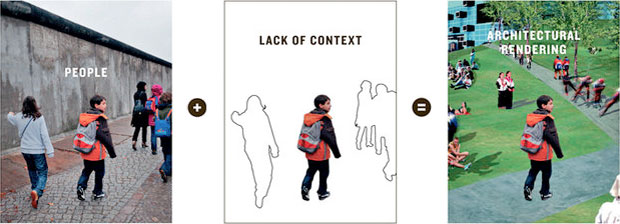

A nice how-to below: adding figures to a scene.

We’ve been having a long conversation with our photographer recently about human figures in architectural photographs and renderings, with that conversation spilling into our design studio as well.

In our view, human figures in an architectural rendering need to remain anonymous. We have previously intimated as much.

Bad examples of architectural presentations use human figures like candy sprinkles on a dessert that’s already too rich, or a liar who talks to much, or buildings that need signs to point out where the front door is. These things don’t help and are not fixes. Just stop.

We do want to see past the sprinkles and think about the scale of the architectural space proposed. We want the verisimilitude, the invitation to a possible future. We don’t want to be distracted by space invaders, thinking about who these people are, where they got their hair cut, or what they might be really thinking about.

Which is why they often turn their backs on us.

Or skulk in the trees.

Or move faster than the shutter speed – feeling safer behind the blur.

Or being ‘lonely in the modern world’ they quietly sigh and wait for us to finish the render.

Or try to quickly move out of the frame.

(N.B. The first three images above we think are pretty good. The last two technically excellent but alienating. Image one is Foster’s Apple campus. The others are all from the developer package selling Renzo Piano’s London Shard project. Mostly good, but some not. Here is an interesting, if scary, example, a scariness relieved only somewhat after reading about the particular and weird building brief, but, still.)

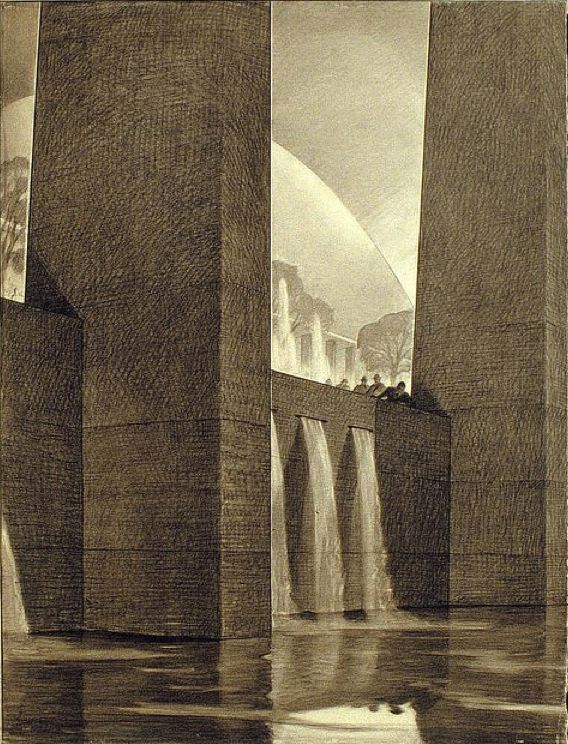

In seriousness, it has always been thus: creating a quality architectural rendering requires training the fine arts, knowledge of color theory, an intuition about perspective and composition, and an understanding of how to reinforce a narrative and communicate visually. In the digital present, days, it also requires the digital skills to correct the fall of light on a figure, to artfully anonymize it, the ability to properly add shadows and reflected light and to feather it into the scene. Even a quick plan sketch is a tangled network of choices of what to foreground and what to background given the intent of the drawing. A representation in three dimensional space more so.

And per the conversation referenced above, figures, people, models – call them what you will – and messaging gone off the rails are just as much a problem for architectural photographers, especially as the line between the photograph and the CGI becomes finer. We don’t want our figures to be made fun of. Oh no.

For Photoshop skills, look for some technical how-to in the video above – with plenty more where that came from. Keys to a beautiful visual narrative can’t really be put into a checklist or tutorial, although many have tried. Critique checklists are sometimes informative. The American Association of Architectural Illustrators has an annual competition – which you’d think one could learn a lot from, but to look at the latest publication there is surprisingly little there there.

The three images below grabbed off our boards, certainly aren’t polished perfection, but we like the speed with which they were created, and how strong a communication tool they are for informal design updates both within a design team and with our clients.

During design, at BDA we find it convenient to render figures directly within Artlantis and take advantage of quickly moving back and forth between active designing and reflective assessment. Post-processing to get the figures right makes for a less efficient workflow – but for important public-record renderings the figures certainly need to be “right”. Packaged 3d scalies or renderable 3d figures are almost never perfect out of the box, but they are perfectly adequate for scenarios where brisk efficiency is more important than perfect photo-realism, which in a busy small design office is… almost all the time. And often we don’t bother with figures at all, knowing that a space can speak for itself if the space is well-designed and well-presented.

Verisimilitude is a slippery slope. Figures can be semi-transparent in-motion ghosts, as in time-lapse photographs, or you can shoot for natural realism, raising the bar and your time commitment by an order of magnitude with the sudden need to get the lighting, palette, composition, composure, and emphasis right. Before you know it, you’re as wrapped up in the blocking as Raphael must have been when painting the School of Athens, although I think we’ll agree his intentions deviate a bit from the intentions of the typical twenty-first century architect rendering a scene.

As it has always been with architectural representation, the goal is to get to the point. Transmit the right message: what the space is like, how the light comes in, how it might feel to be there.