To quote a commissioner in Chicago’s Department of the Environment.

Cities adapt or they go away. Climate change is happening in both real and dramatic ways, but also in slow, pervasive ways. We can handle it, but we do need to acknowledge it. We are on a 50-year cycle, but we need to get going.

So the Chicago of the future will be a city of Sweet Gum and Live Oak.

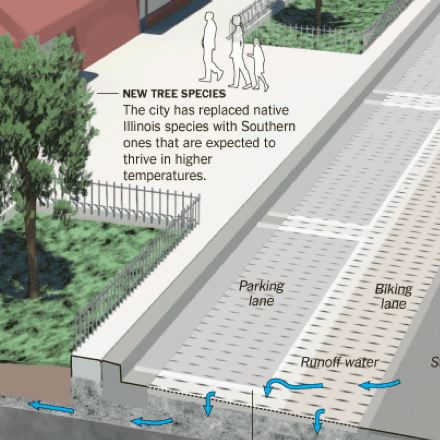

Southern trees have replaced White Oaks (the State Tree of Illinois) and Norway Maples (the most common shade tree in the city today) in city planting lists, as the northern species will no longer be viable in the Windy City’s expected climate at the end of the century.

Beyond adjusting the viable species list for the urban forest, the city’s one hundred year planning horizon calls for today’s paving to be replaced with reflective, permeable designs, black tar rooftops to be replaced with greenroofs, and air conditioning to be added to public schools which today typically don’t need it. All consistent with a hotter, wetter, “great lakes bayou” milieu of 2110.

How does architecture plan for the future? How do our design decisions anticipate and enable longevity of a design?

Creep

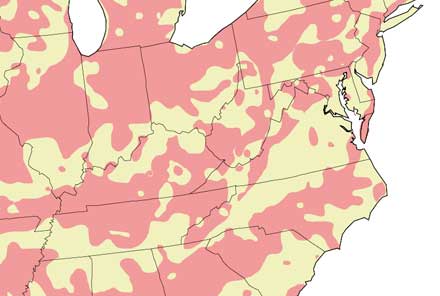

The USDA plant hardiness zone map was last revised in 1990. In 2006, the American Horticultural Society and the National Arbor Day Foundation have issued a revised map showing the northern migration of climate zones. (Given the incendiary nature of climate change politics, especially in Virginia, the USDA has probably decided that discretion is the better part of valor.) The image below highlights areas whose hardiness zone has increased by +1 in the last sixteen years. Please jump over to arborday.org for a look at the time-lapse map image.

Mobile species will, and are currently, following the hardiness zones north. The trees are having a harder time of it.

Buildings, like trees, aren’t all that mobile, and don’t last as long as cities – which is as it should be – urban infrastructure and governments change more slowly than commerce, which changes more slowly than fashion.

Still, our architectural work is multi-generational by most measures: the public building designs produced by our studio will endure for centuries with any luck, the private residences a bit less, and commercial structures – at the scale of our practice – ten to fifty years. Commercial structures at the scale of a Chicago skyscraper are easily multi-generational.

Back in the day, to build for the ages all an architect needed was the skill to develop a reasonably flexible set of spaces able to roll with the punches of changing use over time, and maintainable materials. Barring natural catastrophe, a well-loved and well-maintained building can will last forever. The question of what compels us to “love” a building to the degree that our culture would care for it for generations is best left for another time – but clearly well-loved buildings are the ones that stick around.

Buildings that don’t work, that aren’t loved, that are too hard to maintain, that cannot come to terms with new ways of living are eventually demolished and replaced. It is hard enough to get a design right architecturally for now, let alone get it right for a climate two hundred years in the future. Notoriously chancy as predicting the future may be, to not at least ask ourselves the question of whether our landscape and building design decisions are sustainable moving forward two or three generations, or two or three centuries, even, would seem irresponsible.