analog (also analogue)

noun: a thing seen as comparable to another : the idea that the fertilized egg contains a miniature analog of every adult structure.

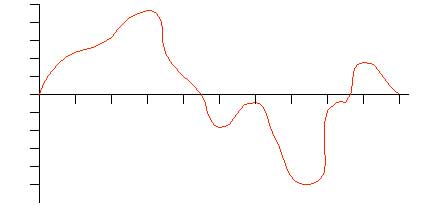

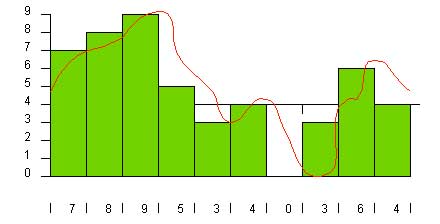

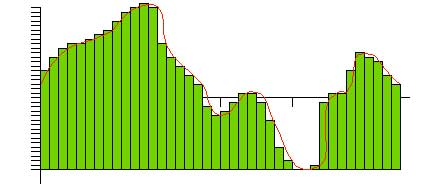

adjective: relating to or using signals or information represented by a continuously variable physical quantity such as spatial position or voltage. Often contrasted with digital.

“The perfection of an approximation vs. an approximation of perfection.”

Audiophiles sum up the digital/analog divide with that little saying. “Perfection of an approximation” accurately describes digital audio sampling or digital images (samples per unit of time, or “sampling” per unit of area as the case may be.) We are visual artists, and we know that at a certain point, increasing DPI is a waste of time and disc space – further detail becomes irrelevant. On the other hand, “Approximation of perfection” doesn’t really make sense unless we’re thinking of the world in the Platonic sense – keeping in mind a perfect and ideal model out there somewhere to which all terrestrial instances aspire to.

Interestingly enough, half the time the analog vs. digital debate is couched in the ability of one technology or the other to capture an experience with fidelity to an “original”: a visual or aural essence captured and conveyed. One wonders if this is even possible. I’m sure there are synthesizers capable of matching the wave-form of a violin perfectly. But why is the music of the “real” violin always more “real”? We listen. We’re in a particular space, with particular company; the wood of the instrument: spruce, maple, and ebony; we think of the skill of the instrument maker, the composer, the player; the horsehair and animal gut under tension; the players mood; we notice the sounds outside and the ambient environment. The air conditioning may or may not be working.

Musical instruments in my book might be the ultimate analog engines. Buildings aspire to their purity.

Anyway – a long introduction about “fidelity after the fact” – which is not really the topic. “Fidelity imbued by process” might be. Analog in the sense of “analogous structures” is more to the point – where a part mirrors the whole in a recursive fractal way, or where metaphor is close, or poetry, or a jump-start on meaning or emotion because something reminds us of something else.

But suddenly, you touch my heart, you do me good, I am happy and I say: ‘This is beautiful.’ That is architecture. Art enters in.

The “approximation” in this case is not the idea of Gothic cathedrals reminding us of forests, or the Renaissance celestial soffit, or modernist piano curves or nautical pipe rails. That’s certainly interesting stuff, but equally interesting is how a brick approximates the size and shape of a human hand and the ability of the human to pick it up, and how those criteria constrain the assembly of the brick wall. We’re interested in how timbers are approximately the length of a tree, and in the origin of the old saw “a building should be the color of the ground upon which it is built”.

How does the physicality of the human body, or of the world, “enter in” to our structures? Why is it now so hard to make an authentic neighborhood or city? Why do hand-made vernacular structures ring true? Or do they? How can a building resonate with the pure tone of a well-made Guarneri or Stradivari? Or can it?

If an approximation is good enough, do we care? Do our buildings benefit if our tools and processes are “grounded” in the real world? Is a pure mathematical construct OK? or even possible?

Dirt

Architectural drawing, all drawing really, is a sensual activity, architectural drawing certainly more so in the past than now. Old drawing tools are dumb little siblings of musical instruments. Nothing “virtual”, everything “actual”: the grit and grain and weight of different paper, the smell of ink, black fingers, the skill involved in drawing a long even line by sliding a clutch pencil “lead” against a straightedge while rotating it to keep the weight of the line consistent, the partnering of surface tension, gravity, and sable hair to pull a watercolor wash down the paper, the pigment of the wash itself ground from mineral and clay. Greek architects drew directly on the stone pulled from the ground, setting dimensions for the most subtle optical adjustments while sitting I presume not too far from the masons swinging hammers and working to those architect’s intentions. Even with cheap imported pens from God-knows-where made of God-knows-what scratching design thoughts on pages in our Moleskine, some of this – uh what are we calling it? – some sort of authenticity? – is still there. Just a little.

Whether drawing or building or making stuff, the analog limitations of materials, and our bodies, once guided and constrained our hands and our thinking. Digital tools open up interesting avenues, no question, but I miss what we’re leaving behind and wonder how it affects our work. Ultimately, I suppose, this is a green idea: regardless of the number of layers of externalization (electricity, machines, industry, consumer economy, software) everything starts, and ends, is made from, and ends back up in, the world.

Todd Williams and Billie Tsien have a really nice riff on this, quoted here from their book Living and Working. bd-MAP is a blog about processes, after all, and they describe theirs very well. The tools, and how you use them, they say, make a difference.

Slowness

…Knud Aerbo, one of Arne Jacobsen’s former associates, spoke of Jacobson’s office:

What we had when we worked with Arne Jacobson: A drawing table – a 90 x 160 cm uneven table top – a side chair with a straw bottom. Our own T-square and a pencil which had to be sharpened with a knife….Drawing pins to hold the paper; tape was not invented yet…. If you look at it today , you will have to say: it could not be done. But luckily we did not know then.

Recently, one of the architects in our studio put down the telephone and said incredulously, “No more leads!” Calling to place an order for new “F” leads, he was told that Faber Castell was no longer making them. People apparently do not draw enough anymore to make it worth their while. This is just the latest disappearance. And it seems to be happening more and more often to more and more tools that we use. Lettering and shape templates are disappearing. In 1993 we were told that there were only 144 more Dietzgen lettering templates in all the warehouses in the United States. So, we bought twenty. The “S”s and “4”s on these templates are wearing out, breaking, and there are no more templates to be had. Because we hear that they too are being phased out, we are hoarding ink pens. It is isolating and disorienting; a very strange feeling, rather like waking up to find that that the tide has come in, and familiar landmarks are submerged. Slowly, the tools of the hand disappear.

In the United States, the practice of architecture has come to rely on the computer. In offices the word efficiency is always mentioned, and in design schools the capability to create and rotate complex forms in space is lauded. So, with surprising speed, the tools of the hand are becoming extinct.

clutch pencil, lead and lead pointer

bunny bag

pounce

erasing shield

lettering template

*soon to disappear

This is a lamentation for lost tools and a quiet manifesto describing our desire for slowness. We write not in opposition to computers – in fact we are in the midst of bringing them into our studio – but rather it is a discussion about the importance of slowness. We write in support of slowness.

“There is a secret bond between slowness and memory, between speed and forgetting. Consider this utterly commonplace situation: a man is walking down the street. At a certain moment, he tries to recall something, but the recollection escapes him. Automatically, he slows down. Meanwhile, a person who wants to forget a disagreeable incident he has just lived through starts unconsciously to speed up his pace, as if he were trying to distance himself from a thing still too close to him in time.

In existential mathematics, that experience takes the form of two basic equations: the degree of slowness is directly proportional to the intensity of memory; the degree of speed is directly proportional to the intensity of forgetting.”

Slowness – Milan Kundera

Slowness of Method

Our desire to continue to use the tools of the hand, even as we may begin to use the computer, has to do with their connection to our bodies. Buildings are still constructed with hands, and it seems that the hand still knows best what the hand is capable of doing. As our hands move, we have the time to think and to observe our actions. We draw using pencil and ink, on mylar and on vellum. When we make changes, they occur with effort and a fair amount of tedious scrubbing with erasers, erasing shields, and spit. We have to sift back through previous drawings and bring them to agreement. So, decisions are made slowly, after thoughtful investigation, because they are a commitment that has consequence. It is better to be slow.

We like to keep the stack of finished and unfinished drawings nearby so that the whole project can be reviewed easily. Their physical presence is evidence of work done, and a reminder of what there is to do. The grime that builds up from being worked over is poignant and satisfying. We see the history of the presence of our hand. To have the actual drawings in reach allows us to understand the project in a more complete and comprehensive way. In the buildings we design, we struggle to achieve a unity and sense of wholeness that can come from a balance of individual gestures within a larger and more singular container. The focus of a computer screen feels too compartmentalized and tight to see and understand the whole. And if every time a change is made, a new printout is made, there is the problem that the printouts are too clean. They don’t show the scrubbed and messy sections of erasure, so there is no evidence to indicate the history of the development of an idea. Crucial to creating wholeness is the understanding of the development of the idea.

We work together, 12 people in one room without divisions. Much like a family, we expect that others will help whenever we need them, and however we need them. So there is no division of labor into design, production, model making or interiors. Each architect is involved in the making of contracts, billing, and writing of letters. Since we have no secretary, the phone is answered by whoever has the least patience with the ringing. Because each person must be a generalist, a certain amount of efficiency is lost, as each person must learn all the tasks of the office. We ask that people constantly shift their attention between their particular task and one which helps the office as a whole. What this rather casual approach to office management accomplishes is that everyone knows what is going on around them. If there is a problem, it is shared, and of course we try to share the joys as well. The sense of well being in the studio must be supported and nurtured by each member.

So our way of working allows us to have the experience of slowness. Tools are connected to the slower capacity of the hand; the presence of hand drawn pages documents both the path of thought and the destination; the generalization of tasks means the office works not as an efficient machine, but as a loose and independent and somewhat inefficient family. The slowness of method allows us breath and breadth.

We have written a Mission Statement for the office:

Whatever we design must be of use, but at the same time transcend its use.

It must be rooted in time and site and client needs but it must transcend time and site and client needs.

We do not want to develop a style or specialize in any project type.

It is our hope to continue to work on only a few projects at a time, with intense personal involvement in all parts of the design and construction. We want the studio to be a good place to work, and learn, and grow, both for the people who work in the office, and for ourselves.

The metaphor for the office is a family. Each person must take responsibility for their own work , but as well must be responsible for the good of the whole. We do not believe in the separation or specialization of skills. Each architect in the office will work through all aspects of a project.

We would like to be financially stable, but this will not outweigh artistic or ethical beliefs, which will always come first.

The work should reflect optimism and love. The spiritual aspect of the work will emerge if the work is done well.

Slowness of Design

In a public forum we were asked, “What is your design strategy?” We were at a loss for words. There is no strategy for either an ascendant career, or more importantly, for the way that we design. It is so easy to use the cushion of past thoughts to soften the terrifying free fall of starting a new project. It is inevitable that as we accumulate a longer design history we repeat things unconsciously. Still, perhaps naively, but in earnest, we try to start each project with a blank slate. The design is incremental – small steps that are made in response to the site, the client, the builder, and our own intuition. We try to fight through what we have learned, toward the freedom found in innocence. The design is a slow and often uneven accumulation of stitches, that are often ripped out part way through while we struggle to make clear, or to understand what the pattern and organization might be, even as we avoid as much as possible knowing what the final image might be.

So, the first intuitive drawings are usually very rough plan forms which might demonstrate the gesture of the body’s movement and how that is expressed by a mass in relationship to the land. We always show these drawings to the client because we want them to understand the intuition or gesture that is the genesis of the design. It is also a way of saying “I don’t know what I am doing yet, but I do have a feeling about it.”

Often, as the plans are worked through, an idea about a section or a detail or a piece of cabinetwork will come to mind. And for a while the plans are put aside and the stray thought is pursued. Progress is a stutter step not a forward march — three steps forward, two to the side, and one step back. It is a choreography that somehow pulls itself together. With each project, it feels as though we are infants learning how to walk. We pull ourselves up, wobble, take a few steps, and fall down.

This way of developing the design mirrors the working method of the office – moving back and forth between advancing the particular task and attending to the myriad details that are the sidetrack. One generally thinks that to be “sidetracked” is a bad condition, but we think that it is enriching. The sidetrack is simply a parallel route.

It has been said that architecture is the mother of all the arts – meaning, one supposes, that it is the generative root. We prefer to think that architecture is like a mother caring for a toddler, who must keep hold of the larger vision of the adult whom the child will become, while stopping to clean up fingerprints and wipe noses.

For us, elevations are always the last part of a building to be developed. Often we are at the end of design development before we even begin to rough out the elevations. This is because elevation drawings close down the process of questioning by making the image of the building too clear, too “graspable” and therefore too final. Clients, magazines, in fact, we as architects and human beings, all want an easy and clear answer. But it is better not to provide one before the interior habitation and the structure of the building has been given enough time to develop as the logic for the facade.

[…]

Finally, during the construction period, the project architect-who has been involved since the beginning intuitive drawings- supervises the construction. Often on larger projects the project architect has moved to the site for as long as a year and half. In this way as questions come up during the course of the project, the choices that are made are made with a sense of the history of the idea and they are true design decisions that accrue to wholeness. They are not simply the result of expediency in the field.

This position of “not knowing a priori” is antithetical to the general model of the architect as hero. This is a damaging model because it discourages the slowness of process that comes from the patient search. Certainty is a prison.

Slowness of Perception

As our work matures, the perception of it is less and less understandable through photographs. One can only understand it by being there and moving and staying still. One reason is that we have been trying to integrate our buildings into the landscape. Thus, often the most important space is the empty space that is contained by the built forms. This empty space is the heart of the project at the Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla. It is the invisible magnet which holds together the separate buildings, and provides the coherence which makes the project feel whole. So what is not there is equally important, perhaps more important than what is there. How does one photograph nothing? One experiences it.

So it comes full circle back to “experience”. Moving in the world, wind and sun on face, perhaps rain, our time and our destinations limited by the body’s ability to get us there. We are physical constructs, as are our buildings. It might be that the best reason working a construction job helps make you a better architect is not that you’ll learn how buildings go together, but rather that you begin to appreciate the scale and weight of materials in gravity, how buildings are made by agreement between people and are therefore a political act, the granular nature of most construction projects – a granularity imposed by the limitations of our bodies, and the machines we use to overcome those limits. Somewhat.

Is it true that in order to make something, something else has to go? Even making something as simple as marks on a piece of paper? The opening stanza in the verse below is a startling zero-sum exchange, like a zen meditation on impermanence, but no more startling than thinking about where the electricity that powers your computer most likely came from, or how the battery for your laptop was made, or how the gold in your cellphone got there, or the origin of asphalt shingles, where the trees were felled, or how the violin got made.

How to Begin

{From a recipe by Ari the Learned in his

twelfth-century Book of the Icelanders}

To make a poem, catch a goat;

Draw a knife across its throat.

When all life has left the creature,

Skin it; dip its hide in water.

Add old lime and stir the pot

Till the mixture seems to clot.

Then throw the clotted stuff away

And add fresh water every day

For a week, in winter more.

When the water’s clean and clear,

Make a frame and stretch the skin,

Set well away from heat and sun.

Let it dry, then moisten it

And scrape the skin when it is wet.

On the flesh side of the skin

Pour fine pumice; rub it in.

Now make the skin tight in the frame.

And wait a day before you trim

The vellum you have made. Then scan

The sky for raven, goose, or swan

(Some bird of size that does not sing)

And pluck a feather from a wing.

A left-wing feather if you can

Because such feathers fit the hand.

For ink, you need the bearberry,

And bark stripped from a willow tree.

Boil the mixture. When you spill

A drop that forms a little ball,

The ink is done. The vellum waits

The issue of the murdered goat,

The plundered raven, swan, and tree,

The music of the bearberry.

‹ rendered by Leonard Woolf

All that, and poor Ari hasn’t even begun, no doubt exhausted from the infernal preparatory activity. But the vellum is ready, and certainly there is a visceral relationship between Ari’s cosmos and his toolset. Next time he’ll probably pay someone to help out with the hard stuff – planting seeds of an economy and a culture in doing so. Then before you know it, the vellum is an iMac, all the hard making done, a digital vellum, waiting the issue of what was pressed into service on our behalf (the plundered raven, goat, swan, and tree), and dreaming, to the extent an iMac can dream, that the ideas transcribed upon its surface will be equal to, or exceed, those parts of the world taken in the making.